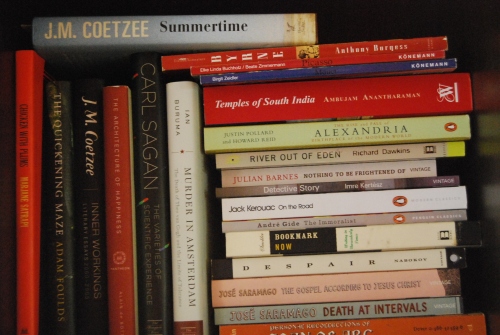

As I mentioned in my last post, the news that Coetzee’s Summertime was released sent me immediately to my favourite local bookstore to get my copy. However, I could get to it only a little later and have just read the last page, a few moments back.

As I mentioned in my last post, the news that Coetzee’s Summertime was released sent me immediately to my favourite local bookstore to get my copy. However, I could get to it only a little later and have just read the last page, a few moments back.

When I first heard about Summertime and its theme, I was intrigued and awaited it patiently. It was due to release only in December 2009, but I guess the publishers wanted to cash in on the media coverage it got due to the Booker Shortlist and released it immediately after the shortlist announcement. As someone who has read and loved Coetzee’s work before, I was not complaining.

Summertime had to be a difficult book, for any memoir is difficult. However, Coetzee was no novice in the genre with Boyhood and Youth having been received well before. Still, Summertime had to be difficult. Unfortunately, that shows when you read the book as well.

Coetzee is a master of words, the nobel prize has confirmed it sometime back. For someone as accomplished in his art as Coetzee, his last novel was an inevitable experiment. A fiction that speaks through dated diary entries, without any character voice, Diary of a Bad Year was an achievement as well. While Summertime is different for sure, it is that same experiment taken forward.

As someone who starts a story every 15 days and has never finished any, I do understand in my limited capacity the pain, discipline, and frustration of baking the final batter. You will see that Coetzee for some reason did not want to go through this process and has served you the batter with no apologies. Summertime is a half attempt. It is not that batter cannot be eaten, but cakes taste better. As one of the characters through whom Coetzee chooses to give a glimpse of himself remarks – Too cool, too neat, I would say. Too easy. Too lacking in passion.

One of the reason I found this was a lazy attempt is because the other works of his that I have read have left me in awe of him. From that pedestal, Summertime lacks warmth. It is no news that Coetzee shares little about himself or his inspirations in real life. He, I believe, is from the school of thought that does not have faith in public images of authors. With Summertime, Coetzee has taken that inhibition to his fiction as well. While I empathize with the thought that an author’s life has little to do with his works, my question is – Why write a memoir/biographical fiction then?

4 women, 1 colleague/friend, few dated diary entries, and a few undated fragments are what he has chosen as reflections of himself. Summertime begins with the diary entries which give a glimpse into the thoughts of Coetzee in the period (1972-1977) in which the memoir is set. A young biographer is writing a book on the nobel laureate John Coetzee, a white South African author who has recently died in Australia. The second part of the book is an interview the biographer conducts with a women named Julia. She is married, a mother and just out of adventure, gets into an adultrous relationship with Coetzee. She lives in the same neighborhood where Coetzee stays with his father. This part is in the form of an interview, though the questions are few and short and therefore the answers are more like narrations.

The third part of the book involves Margot, a cousin and childhood love of Coetzee. The biographer had interviewed her and is now reading out the narrative that he has culled out from her

Coetzee at the Nobel Ceremony

answers. This, I believe, is the most powerful narrative in the book. Coetzee probably intended it so, as it is clear from the words Coetzee chooses to put in Margot’s mouth that she was the alternate that he never was. The only relationship where Coetzee admits some warmth is with Margot, the alter-ego which remained as cut-off from his real self as everyone else.

Adriana, mother of a young beautiful girl whom Coetzee teaches English in extra classes, is the most intriguing of all. In her testimony, Coetzee was in love with her and troubles her to no end. However, she cannot be trusted. Adriana is an emotion that intrigues Coetzee and he presents it to us in all its raw contradictions. He then moves to a colleague/friend who taught in the same university. He is the only person of the same sex that he chose to include, though very briefly, as his mirror. There is not much to suggest as to why is he the one man in company of four rather complex women from his life. You are only left guessing. The last mirror is a lady lecturer from France with whom he taught a course in African literature and had sexual relations for sometime. She is the one who talks about his writing, his books – but too little, yet again. It is almost like Coetzee wrote Summertime to tease his readers, his so called ‘admirers’.

Summertime is not as dry as it may sound from whatever I have said above. Despite all this, it is a book you will read through easily. It has underlying themes of life, of a father-son relationship, of the commerce of life and the soul that pays in the bargain. It is an insight into how lonely a thinking, writing soul can be. It also is a relevant insight into the complex psyche of the white South Africans who were not a part of apartheid but were silently accommodating nonetheless.

Summertime lacks nothing when it comes to Coetzee’s ability to put the right words in the right order to make the right strings in your heart or head play the right tune. But it does lack the richness of a Coetzee fiction. It is a biographical fiction by an author who does not want to tell you anything about himself after he started writing. With that disclaimer, it is not a book to let go. Though, if you have not read Coetzee before, go pick his other works. Summertime can wait.

2008. Thanks to a lot of

2008. Thanks to a lot of  by women that makes Golden Notebook relevant even after decades of its first publication. I consider Colin Wilson’s

by women that makes Golden Notebook relevant even after decades of its first publication. I consider Colin Wilson’s  Sometimes, all roads lead to Rome, no matter what. After watching

Sometimes, all roads lead to Rome, no matter what. After watching