As an Indian who grew up in India with no interaction with the rest of the world, Kashmir was a fantasy land of beauty. However, while every summer holiday my parents picked a destination for our next trip, I used to wonder why Kashmir was never on the map. I never asked, because without knowing much it was well understood in the early 90s that Kashmir was forbidden fruit. Pakistan was the villain and the Indian government (the hero) was saving the poor Kashmiris from the Villains incessant acts of interference.

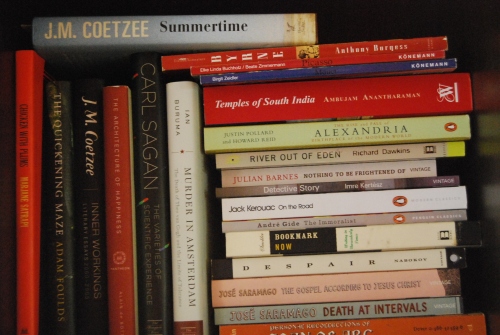

Like it or not, I grew up. I started reading and pretty much got hooked to it. My childhood beliefs were violated in many respects, with total disregard to my innocence. While I had come to believe in the crystal clear position regarding Kashmir – as told to us from India by Indians, I encountered phrases like “India occupied Kashmir”. I took offense and grew violently Indian in my views regarding the issue. I came to then believe that the Villain had got the international community on its side and the poor hero (which still was the Indian state for me) was having a tough time proving the truth. It is probably in the nature of truth to be elusive, and India became more of a superhero for me to be standing on the right side of this ambition. However, the superhero status of India was challenged practically everyday – stories of military excesses by the Indian army, stories of Kashmiris not wanting to be a part of India, stories of Nehru’s quixotic enthusiasm in promising a plebiscite and India not honoring it, etc. My defence mechanism to these stories was the same as I had to deal with the allegation of original sin having marked the human race – these were just stories.

Then something happened. To put it precisely, Bill Clinton happened. He came to India in March 2000. Despite India’s insistence on Kashmir being an internal issue, requiring no international interference or debate, we always made an exception for Uncle Sam. Uncle Sam symbolizes money, the one point passion of all developing nations including India in the contemporary times. We bend over backwards to please them; therefore, when they talk Kashmir, we forget our stand and talk back. Clinton’s visit was literally a celebrated event in India. India wanted to impress. Like young couples want to do everything to impress when their parents first visit them in their new house, India was filled with joy and nervousness. The visit went well, except for a small irritant – 36 Sikhs were massacred in Chittisinghpura in Kashmir on the eve of Clinton’s visit. There are two theories on this massacre – first, and the comfortable one to admit, that Pakistani terrorists dressed as Indian military was responsible for it. The second theory is the not so innocent one; the kind of story which robs children of their heroes and superheroes (whether they are true or not), the kind that devastates the belief in Santa. This theory, in detail studied and supported by Pankaj Mishra in the New York Review of books suggests that this was indeed the Indian military working to create the headline for the next day’s newspaper that Uncle Sam would have in his hand when he lands in India.

The Chittsinghpura massacre was solved, like every single terrorist act has been solved when it happens in Kashmir but never when it happens in the mainland India. Within a week of any terrorist act in Kashmir, there are five young Kashmiri muslims killed and flashed to the media as those responsible for the act. The same happened here, though no one (except Indians) believed them this time. It was different. In a decade long history of violence in Kashmir, the militants had left the Sikhs alone. Their fight was with the Hindus and the Indian state and they did not consider Sikhs a part of that fight. To change that stand a day before Uncle Sam (whom the militants aka Pakistan wants to impress as well) lands to declare who is right and who is not, sounded improbable. There are many sides to this story and the truth, as elusive as it always remains, will never be known. But what is true is that The Hindu (a respected Indian newspaper published dominantly from the southern parts) reprinted the Pankaj Mishra article and unfortunately, I was robbed of my innocence. I did not believe, like a true Indian, that our army could ever do this. But I felt like a mother who spots a used condom in her daughter’s wastebin when she returns after a weekend away. Pankaj Mishra’s article has haunted me ever since.

The net effect of Mishra’s article was not that I changed sides, but that an element of doubt was planted in me beyond repair. From then on, whenever violence in Kashmir was reported and the perpetrators gunned down within a week, instead of being happy as I used to be, I felt a kind of bad aftertaste in my mouth.

Eventually, what started in the 90s continues till date. Violence in Kashmir is so common that it is not even worthy of a news clipping. Now, the only time Indians and the Indian media talk of Kashmir is when Kashmiris come out of their homes to abuse India – the separatist movement as we call it. It has happened at very regular intervals in the last couple of years. Indian policy makers dispatch a group of citizens to talk. The principle remains, any solution to the Kashmir issue shall be within the frameworks of the Indian constitution. While this stand was respected and agreed to by a substantial minority till a decade back, today the Kashmiris spit on the Indian constitution – almost unanimously. The alienation is complete. It is only not apparent to the Indians who have guarded their innocence about Kashmir against all odds. The harsh truth is that an overwhelming majority of Indians don’t give a dead rat’s ass about Kashmir as long as no one talk’s about Kashmir not being an integral part of India. Kashmir for India is a valued possession, nothing else. It is like the first Barbie doll that most girls keep for life, even though it remains rotting in some obscure cartons of long forgotten memorabilia.

One citizen of India became vocal about her support to the cause of the Kashmiris a few years back. Thanks to the fact that she has a gift for stringing words together like very few do, she had won the Booker prize in 1997. India was proud of her – unanimously so. No matter if most of us never read a single page of her novel, we had an opinion of her – she was one of the very few Indians to have won the Booker and was a matter of pride for the Indians. She commands attention in international media due to this. This was again a matter of pride. All this is the reason why it is so painful when this pride of Indian changed sides. She started criticizing the Indian state. She became the voice of dissent. Net result – we stopped reading her and started criticizing her. It went to the point where the attempt is now more to dismiss her as a crackhead than to debate what she says. She is now the enemy of the collective of innocent Indian citizens. Problem is, they don’t feel that innocent anymore. Arundhati Roy’s criticism of the Indian state carries with it a not so subtle judgment on the Indian people and their apathy. As a result, Indians are literally up in arms against her. How dare she! Turning a deaf ear and shouting at the top of one’s voice, so as not to be heard but not to hear, is the first symptom of guilt.

I hated Arundhati Roy’s first piece of dissent when she attacked the Indian nuclear tests. She commented that nuclear weapons were human race’s proclamation to the gods that what he took ages to build, we could destroy in a minute. I disagreed. Nuclear weapons are evil, not even Uncle Sam would dare deny that. However, much before India had them, others did. And the world could be destroyed in minutes even if India did not carry those tests. However, a recent re-reading of that article made me see it in another light. The argument is not that India created nuclear weapons; the argument is that in choosing to do the tests, India sided with the evil. It accepted nuclear weapons. The argument is why not be like Japan when it comes to nuclear weapons. And it is a valid argument. It is like a child’s disappointment when their parents are seen taking the not so moral route and being ‘practical’.

Arundhati got very involved with the Narmada dam issue and wrote several essays on the extraordinary impact it would have on thousands of people who would be displaced. It was a valid dissenting voice which sided with the rights of the people, most of whom neither had the means nor the intellect to be heard, against the mad rush for ‘development’ and the capital it represented. She criticized the Supreme Court’s decision on the Public Interest Litigation on the issue and was held in contempt, though with a suspended one day sentence. That was symbolic of the Indian psyche – we are not sure if you right. We don’t want to believe you have a point. So we will proclaim that you are wrong, but won’t go so far as to punish you for it, because we need to have some semblance of justice.

Then Arundhati told the story of the Indian Maoists (more of a violent tribal rights movement) with amazing empathy. By now, no one cared. Maoists were the bad guys, they used violence. This gave the Indians the right to dismiss Arundhati as a dissenter for the sake of dissent. She was labeled as a media hungry crazy owl who doctored her opinions to be shocking so that it would attract attention. Maoists were not debatable, Arundhati was crazy and the Indians lived their lives in unlivable cities without any further concern. Who cares about some tribals who were denied basic rights. As long as they peacefully objected, our hearts would go out to them. Once they started killing, they lost the cause. No need to think of the fact that when they were peaceful none in India knew of anything about violation of their rights. When they made noise with bombs, they crossed a line and we stuffed our ears with ‘nothing justifies violence’. Was Subhash Chandra Bose justified? Shut up! Don’t talk crazy. And there goes all credibility of Arundhati Roy, for ever.

Arundhati, however, was not done. She now spoke on Kashmir. Behold! She made a call for the freedom of Kashmir from ‘Indian military occupation’. She did this two years back. Then now, just before the even more charming Uncle Sam (with an anticipatory Noble under his belt) arrives in India, Arundhati shared platform with the separatist leaders of Kashmir and herself gave a call for it – the unspeakable freedom of Kashmir. Woah! Talk of lines! This was way beyond the line of control. How could my sister argue I throw away my first Barbie? And to incite a mob to take it away from me? This was sedition – plain and simple.

As expected the Indian media, the Indian people (the one that doesn’t give a dead rat’s ass…) and of course the Indian politicians are up in arms against this seditious unruly idiot of a woman whom they had dismissed as a crazy owl sometime back. Not a word has been spoken about the debate that this must have triggered. Not a word about the military excesses we have made in Kashmir. Not a word about the life of the Kashmiris, which even if viewed from the Article 21 angle of the Indian constitution, has long been lost.

Indians are fighting a lost battle. They refuse to think outside the box, the box being the Indian constitution. Unfortunately, they now want to stop anyone else living in India to think beyond the box.

I say, we have crossed a line. We did in a creeping manner when for 20 years we allowed Kashmir to be wounded and to have no option but to lick their wounds. Even if we dismiss Indian excesses, which we should not, India has lost all moral rights over Kashmir by its apathy. The only manner in which it can and still holds on to that first Barbie doll is through an unacceptable military occupation. I thought this would shock the conscience of Indians. I thought at least by now, the Indian government will find itself alone. Maybe I had misplaced trust in humanity, specially those of the Indians. I believed that only people of America could live with a Guantanamo Bay in their backyard; my incessant pride at the Indian culture made me believe that we could not. It seems we can. Yes, we can!

As I mentioned in my

As I mentioned in my

2008. Thanks to a lot of

2008. Thanks to a lot of  by women that makes Golden Notebook relevant even after decades of its first publication. I consider Colin Wilson’s

by women that makes Golden Notebook relevant even after decades of its first publication. I consider Colin Wilson’s  Sometimes, all roads lead to Rome, no matter what. After watching

Sometimes, all roads lead to Rome, no matter what. After watching